The Hunterian’s new major exhibition, which opens today, celebrates and analyses its founder William Hunter who was born 300 years ago this year. Hunter was many things – anatomist, royal physician, bibliophile, collector, historian, patron of the arts, teacher – and this exhibition sets out to explore the various aspects of his life and legacy as well as the meaning of the museum he developed throughout his life.

The Hunterian’s new major exhibition, which opens today, celebrates and analyses its founder William Hunter who was born 300 years ago this year. Hunter was many things – anatomist, royal physician, bibliophile, collector, historian, patron of the arts, teacher – and this exhibition sets out to explore the various aspects of his life and legacy as well as the meaning of the museum he developed throughout his life.

Hunter bequeathed his extensive collections of objects, paintings, anatomical specimens, drawings, manuscripts, and books to the University of Glasgow where they have been since they arrived in 1807. The Hunterian Museum was first housed in a purpose-built building designed by William Stark, the first public museum in Scotland, until its collections were dispersed across the various departments of the University when it moved across the city to Gilmorehill in 1870. This exhibition brings together a selection of items from Hunter’s collections for the first time in well over a century. One imagines old friends gathering for a reunion.

The current exhibition is structured around nine inter-relating themes from Hunter’s life and activities with on introductory section, including a comprehensive timeline to provide context about Hunter and his museum. Hunter was born and raised in Scotland and moved to London in the 1740s to complete his medical training and make his fortune.

Room One describes Hunter’s education in at the University of Glasgow (with Professor Francis Hutcheson) and Edinburgh (with Alexander Monro primus) and introduces Hunter’s network of personal and professional friends who included Adam Smith and David Hume. The famous Allan Ramsay portrait of Hunter in his blue velvet coat – the earliest known and dating from the mid-1760s when Hunter’s reputation and fame were growing – takes pride of place.

Room Two relates how Hunter moved to London to complete his medical studies in the 1740s. He trained with the obstetrician William Smellie and became an anatomical assistant the James Douglas thereby maintaining his Scottish links. He also met Richard Mead, one of the leading physician collectors (‘…books for Mead, and butterflies for Sloane…’ – Pope) who provided inspiration and from whose collection Hunter bought extensively after his death. Hunter studied in Paris in 1742 and visited the Continent again in 1748 where he met Professor Bernard Siegfried Albinus, Professor of the Practice of Medicine at Leiden. (He later had many of Albinus’s books in his library.) He also began to buy ‘scare old books’ for his personal library.

Studies complete, Hunter was ready for medical practice. Room Three shows how his career developed. He was a great success, specialising in obstetrics. He became a Royal Physician to Queen Charlotte in 1762 and attended her through 14 (!) pregnancies. He began to develop his collection of anatomical specimens which he used in teaching. He gave anatomical lectures at his home and museum in Great Windmill Street, London.

Room Four explores Hunter as an anatomist and shows how he developed his ideas about the relationship between science and art. He became the first professor of anatomy at the Royal Academy. In his lectures to artists, he insisted that artists had to understand the structure of the body. His collection of anatomical specimens, drawings, and casts aided his medical students but also artists at all stages of their careers.

Room Five displays the theme for which Hunter is best-known today. In 1774, he published The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uteris. This major work of the Enlightenment was based on decades of research. Hunter commissioned artists and worked with a team of anatomists, including his brother John, to create plaster casts and anatomical preparations documenting the stages of human gestation. He worked with the printer John Baskerville to publish masterwork of anatomy. Not for the squeamish, the room features Hunter’s original plaster casts made from the life (or rather death) of women and fetuses and vivid red chalk drawings by the artist Jan van Rymsdyk. A copy of the book is part of the display and testifies to the collaborative effort of anatomists, artists, engravers, and printers led by Hunter.

Room Six focuses on Hunter’s interest in comparative anatomy and features some of the anatomical preparations he used in his teaching. Hunter commissioned George Stubbs, an artist known for his attention to anatomy and accuracy, to paint pictures of ‘exotic’ animals including a nilgai, a moose, and a blackbuck. Hunter used the portrait of the nilgai as a prop when he delivered a paper about the creature to the Royal Society. For Hunter, the work of art was also a tool for understanding his scientific study.

Room Seven demonstrates the worldwide scope of Hunter’s collection. It shows his interest in what he might have called the ‘curious’. Here we find manuscripts of foreign religions, early printed books, coins, ethnographic materials brought back from Captain Cook’s missions of exploration, insects, and shells. Hunter used his extensive network of contacts to acquire interesting and beautiful things from around the word.

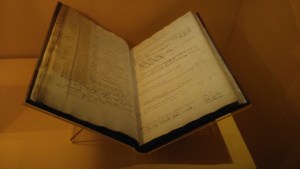

Room Eight shows how Hunter and his assistant documented and ordered Hunter’s treasures. The specimens of all sorts – from drawers filled with types of bees to minerals – were all meant for research and teaching. Hunter and his team prepared and catalogued the variety of things which have now been transmitted to us in the form of a museum. This room also includes one of Hunter’s own library catalogues, his ‘Common Catalogue’ which he used to list his books on non-medical subjects. (You can find out more about Hunter’s library catalogues and library here.)

Room Nine reveals Hunter’s mission to have his collections survive him as a resource for public education. In 1765, having failed to get backing for an institution in his ‘darling London’, he wrote to his mentor William Cullen saying, ‘I have a great inclination to do something at Glasgow’. Glasgow was thinking the same having recognised its need for a collection like Hunter’s. Hunter’s will bequeathed his collections to the University of Glasgow on the condition that his nephew Matthew Baillie would have the use of it first which explains the delay between Hunter’s death and the foundation of the Hunterian.

Finally, Room Ten offers a meditation on ‘Memory’, ‘Reason’, and ‘Imagination’; the anatomy of the modern museum. The eighteenth-century Encyclopédie used these headings to give categories to human knowledge and the room brings examples of the three headings together. Here we see glittering manuscripts and coins, anatomical specimens and drawings, ethnographic materials, paintings, a mastodon tooth… The exhibition finishes with the only known image of the inside of Hunter’s museum at Great Windmill Street. Room Ten is probably the closest we can get to the feeling and the mood of Hunter’s museum as it was when he owned it. Its various and useful objects are presided over by Hunter’s copy of the second edition of the Encyclopédie itself.

The exhibition is absorbing and intriguing. No prior knowledge of Hunter is required. It has something for everyone from those interested in the history of medicine to art lovers to anyone in possession of a curious mind. There are no captions. Instead, visitors are guided using a small booklet. One small problem is that some areas of the display are low-lighted for conservation reasons so it can be difficult to read the text for those of us above a certain age. If you have a small book light, it may be worth bringing along. It is also worth mentioning that presenting this same booklet in the shop earns a substantial discount on the exhibition catalogue. (RRP £50; £39.99 with booklet – see the last page of the booklet.)

I should also mention that my visit was during the private view/launch and some of the items were not yet on display. You can follow the exhibition and see plenty of images at #Hunter300

The exhibition runs from 28 September 2018 to 6 January 2019. It will move to the Yale Center for British Art in Newhaven, CT in February next year.

For opening hours, events, and more see the exhibition website: https://www.gla.ac.uk/hunterian/visit/exhibitions/exhibitionprogramme/williamhunterandtheanatomyofthemodernmuseum/#/